| 1 | Grotte de Montespan, France |

The caving techniques of 1924 were light years away from now. Instead of a high powered torch embedded in a helmet, the most famous cavers like Norbert Casteret could hope for was a match which they prayed wouldn’t be extinguished by a falling drop of water.

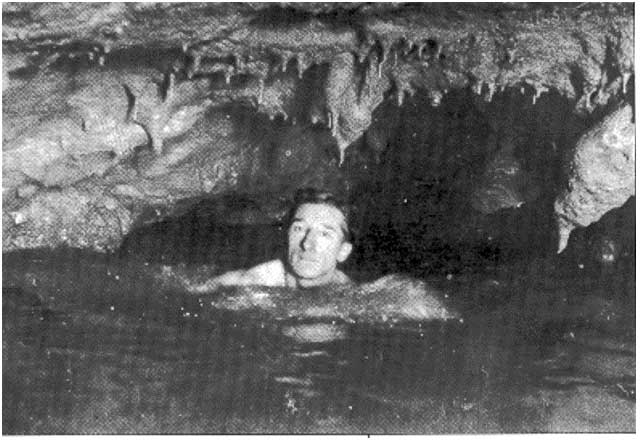

When Casteret told the villagers of Montespan about a local cave he planned to explore in January 1923, they laughed and said “you’ll never get out alive again”. Indeed, when Casteret arrived, he found that halfway through, a river rose to meet the roof. He knew that he could drown, but Casteret had buckets of enthusiasm, and down he went. Miraculously, the flooded section did surface again, but the chamber was pitch black, and the water was already rising. One year later, Casteret returned to Montespan cave for round 2, this time with his assistant Henri Goodin. They breached the flooded passage, and reached Casteret’s old furthest point, before finding a new passage leading to an entirely new cave. Inside, they discovered a hall of cave paintings, including bears and horses.

But the most amazing discovery of all was a life size stone carving of a bear, with one caveat – it was missing its head. The body was embedded with spear marks, like a primitive ritual had been conducted. Casteret was amazed – risking his life had been worth it.

The plot thickened when the duo found a real bear skull between the forepaws of this sculpture. Casteret had some rudimentary archaeological knowledge, and estimated that it was 20,000 years old.

Casteret then summoned experts, and left the bear head in place while he and Godin dug a small channel to relieve the cave’s constant flooding. When he returned to the skull, it was gone! The bear chamber itself was unaffected by the rising river, so theft was the only explanation – or something more ancient, more superstitious.

| 2 | Inchnadamph Bone Caves, Scotland |

Some bear remains are unearthed in mere minutes, but this skeleton took a full 12 years to fully retrieve. The Scottish hamlet of Inchnadamph is famous for its “bones cave”, with the entrance located at the foot of a high mountainside cliff. Discoveries include lynx bones, human skeletons, and the only confirmed evidence of polar bears on British soil.

Most importantly, the cave is home to Uamh an Claonaite, the longest cave passage in Scotland (measuring 1.782 miles), and it was here that professional cavers discovered an ancient brown bear bone back in 1995. Archaeologists declared it to be 11,000 years old, having perished while in hibernation. But where was the rest of the skeleton? From 1995 to 2008, cavers worked flat out to excavate new tunnels, shifting soil and crawling through tiny passages to reveal entire new chambers.

Since Uamh an Claonaite is a dry cave system, there was only a minimal risk of flooding and drowning. Gradually, the team found the bear’s skull, its lower mandible, its vertebra, and its ribs. A few pelvis, foot and limb bones were discovered as well, with the end result that 70-80% of the prehistoric bear’s skeleton was completed. Analysis confirmed it to be a brown bear, rather than a cave bear.

Clearly, centuries of rainwater had gradually washed the bear’s bones down to the lower passages. It was probably an elderly bear who had entered a higher cave entrance in the system, but been too thin to survive the long, cold winter.

| 3 | Ailwee Cave, Island |

Without a dog escaping from its owner, this ancient bear cave could have still been a secret today. In 1943, Jacko McGann was chasing after his pooch in western Ireland, when he spotted a narrow slit in the rocky slopes of Ailwee hill. He explored the cave, but for some reason forget to tell professional cavers about it until 1973. The cavers rushed there instantly, and soon discovered a lengthy passageway, which was initially blocked by boulder fall approximately 230 metres down, but eventually turned out to be 1km long.

Ailwee cave boasts a large underground river, rock formations galore, and three main chambers: Mud Hall, the Cascade Chamber, and Bear Haven. Can you guess what the latter contained? A large brown bear skull, dating back 10,4000 years. Ireland isn’t known for its bear fossils, and it was once doubted whether brown bears had ever lived there, but Ailwee cave has a grand total of 450 bear bones among 15,000 total bones.

In 2006, archaeologists were shocked when a tibia was dated back to 46000 years ago, proving that multiple bears had inhabited the cave. Cuts on the bones proved that ancient hunter gatherers had sliced meat from the carcasses. One thing’s for certain – these guys didn’t expect their handiwork to be stumbled upon 4600 years later.

Tour guides love to tell visitors that Ailwee cave was the last ever bear den to exist in Ireland. Are they correct? Nobody knows.

| 4 | Grotte du Bichon, Switzerland |

Many centuries ago, a prehistoric hunter crept up a steep mountainside in the Swiss Jura, draped in luxurious animal fur. He was stalking a female bear, which his tribe had spotted roaming the wilderness over the last few days. Now, he finally had his prey in his sites, and raising his spear, he threw the most accurate shot his arm could manage. His aim was true – the flint drove into the bear’s spine, causing it to yelp in pain and vanish into a nearby cave.

The hunter wasn’t sure that the bear was truly injured, and not wanting to lose his prize, he deployed a trick he knew well, sparking up a fire to smoke the bear out of its hiding place. But the hunter made one fatal mistake. He crept too close to the cave, and suddenly, the dying bear propelled itself from the darkness, in a final bid for revenge. It collided with the hunter, knocked him to the floor, and before he could cry for help, the hunter was being mauled. Hours later, both man and beast were dead.

For 10,000 years, man and bear lay undiscovered in the heart of the Jura mountains. Until 1956 that is, when a clean cut Westerner found the ancient hunter and bear’s skeletons, still intermingled approximately 15 metres from the cave’s entrance.

At first, the skeletons were a complete mystery, but the discovery of a flint still embedded in the bear’s 3rd vertebrae changed everything, as did charcoal from the fire and 9 other ancient arrowheads strewn around. Both skeletons were dated back to 13,600 years ago, and the skull shape proved that it was a female brown bear, rather than an extinct cave bear.

Today, the cave is a renowned archaeological site, and its name is Grotte Du Bichon. The entrance is at 846 metres in altitude and lies 5 miles north of the Swiss city of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

| 5 | Victoria Cave, Yorkshire |

Another cave discovered by an adventurous stray dog, which vanished down a supposed foxhole in the rugged Yorkshire countryside back in 1837. When 24 year old Michael Horner crawled in after it, he emerged minutes later with his arms full of archaeological artefacts, including multiple ancient coins. One particularly eye catching discovery was a giant bear skull.

The distinctive jaw and forehead shape proved it to be a brown bear rather than a cave bear, and its age was estimated at 14,100 years. Archaeological excavation showed that the mother bear died soon after childbirth, and that the cave was mostly the haunt of adult and juvenile bears.

For once, the skull wasn’t stolen or lost – it currently lives in the Tot Lord collection of Yorkshire. While human remains were also found, including a harpoon made from a reindeer antler, there’s no sign of cutwork on the bear’s skull, hinting that it wandered into the cool, damp cave naturally. The most shocking fossil of all was a hippopotamus, dating back 140,000 years.

Over time, fossil evidence for 7 bears was discovered in Victoria cave, mostly from before the Holocene period that started 11,650 years ago. It’s believed that Yorkshire was one of Britain’s main prehistoric brown bear hubs. The cave itself has a large artificial entrance these days, excavated in 1838, but the original slit where Horner entered still exists.

| 6 | Alpine caves |

On a journey through the European alps 6000 years ago, in the days of Otzi the iceman, your chances of seeing a brown bear would have been 99%. These days, alpine bears are almost extinct, yet the caves containing their remains are too numerous to count.

The Feistringhöhle, for example, is located near Hochswab in the central Austrian region of Styria. In 1963, explorers discovered the large skeletons of three brown bears alongside an arrowhead, as though one of the bears had fled into the cave from primitive hunters before succumbing to its wounds. The Wildes Loch cave is also located in Styria, and bear skeletons were unearthed during excavations in 1856 and 1857. They were stuck in a deep pit, and strangely, the bones began to disappear over the years.

The most gruesome discovery was perhaps the eerie Schwalmis-Bärenhöhle of Switzerland. During the first explorations in 1965, cavers found a brown bear skeleton in the deepest point of the cave (known as the Bärenfalle) with a broken left lower jawbone, surrounded by scratch marks in the rock layers. It was theorised to have fallen into the pit and struggled to excavate itself, before slowly dying of starvation.

Grotta d’Ernesta in Italy has one of the oldest skeletons, dated to 11,900 years ago. This male brown bear was found in 1994, at the very back of the cool, damp cave, as though it had entered hibernation and never woken up.

| 7 | El Capitan, Alaska |

The largest known cave in Alaska, and the first fossil cave to be discovered on Prince of Wales Island. In 1990, explorer Kevin Allred was re-exploring the established upper section of the cave, when suddenly, he stumbled across an undiscovered passage.

Creeping inside, he noticed that the floor was littered with bear fossils, with the highlight being a nearly complete black bear skeleton. Its toes were still in their correct anatomical positions, but surprisingly, tests by archaeologists revealed the skeleton to be 10,750 years old. The next fossil was even more shocking – a grizzly bear so gigantic that they wrongly assigned it to the extinct short-faced bear species (which weighed in at 3000 pounds).

This grizzly skeleton dated back 9670 years, whereas nowadays, Prince of Wales Island has no grizzly bears whatsoever. This could have been a humungous subspecies which no longer exists, failing to migrate southwards into North America. Its bones were scattered across the floor, close to a second entrance which had naturally sealed. A smaller brown bear skeleton was also found, dating back 12,295 years, covered with deep chew marks, clearly coming from a grizzly. The signs were clear: this was an ancient hideout for vicious cannibal bears. The cave also contained two more animals which no longer live on the island: a 10,050 year old red fox, and a small wolverine tooth.

| 8 | Velfjord bear cave, Norway |

Maybe you’re feeling inspired to get out there and find an ancient bear skeleton yourself. If so, then great news – fresh skeletons are being found to this day, and one example was a Scandinavian skeleton discovered in a cave near Vestfold, Norway back in 2016. This cave is extremely remote, located on what was possibly the brown bears’ frigid northerly migration route. The fossils dated back 8000 years, making them the oldest yet found in northern Scandinavia. Because the bones showed no signs of cutting or chewing, the ancient bear had probably ventured in for shelter. Perhaps it was an old bear who had been outcompeted for food that summer, or maybe it was diseased.

What’s more, the cave’s walls were covered with black charcoal. It seemed that primitive humans had tried to flush the bear out using choking plumes of smoke. The charcoal was dated back to the Roman era 2000 years ago, versus 8000 for the fossil, so this was clearly another bear using the same shelter 6000 years later (maybe a distant descendant).

Today, Norway has only 250 brown bears, but the cave is still extremely remote, which is why the bones were only discovered 5 years ago. It’s perfectly conceivable that an absentminded visitor could turn around and get a bear-shaped shock even today.

| 9 | Bumper cave, Alaska |

In 1994, archaeologists pressed ahead and discovered a second bear cave on Prince of Wales Island, this time in the island’s north. It was dubbed Bumper Cave, and soon Dr Timothy Heaton and Dave Love were dispatched to the cave’s mountainous entrance, assisted by gear flown in via helicopter.

They scrambled through the first muddy crawlspace, and entered a low horizonal passage filled with rocks and dirt, and numerous poorly preserved bear bones. They squeezed through a second ultra tight crawlspace, and now they’d hit the jackpot, discovering a number of far better preserved bear skeletons. At the back of the room was a 2 meter ledge which led to a fast flowing stream and a rocky platform. There, Heaton and Love found an almost complete brown bear skeleton, which was clearly female and later dated back to 11,645YA.

A few bones had been washed into the depths of the mountain by the stream, never to be seen again, but the only large bone missing was the lower jaw. Lying next to the skeleton were 2 cubs. There was no sign of predator attack – this was another unfortunate bear family which had perished during hibernation.

Over the next ten days, Heaton and Love discovered 10 brown bear fossils in Bumper Cave, plus a single claw of a black bear. One jawbone was dated to 7025 years ago, the latest ever found on Prince Wales Island – could this have been the final extinction date for the island’s bears?

| 10 | Darband Cave, Iran |

An Iranian bear cave, located in a sandy-coloured canyon with blades of green vegetation swaying at its foot. Darband has two main passages: a shorter cave measuring 30 metres and a longer one measuring 60 metres. With a large square entrance easily visible from over a mile away, Darband has been home to countless animals over the years; its many skeletons include extinct cave bears, deer, wolves, wild goats, and brown bears themselves.

Very few of the bear bones have cut marks, so Darband cave was probably a natural refuge for bears in prehistoric times. These days, Darband cave is as dry as a bone, but travertine limestone deposits prove that a stream once flowed through the middle, which would have given any sheltering bears a nice, clean water supply.

That said, the occasional bone does have a burn mark – could Darband have been a ritual cave? In 2005, artefacts made from terracotta clay were also discovered. An expedition in April 2021 unearthed dozens of animal fossils, plus a human made axe (who else makes them?).

The bear bones in Darband cave have probably been accumulating for hundreds of thousands of years. Imagine what a superstitious local shepherd would have thought if he’d stumbled in one morning.

Leave a Reply