| 1 | In the beginning |

The most famous Grizzly Man of all time was undoubtedly Timothy Treadwell, who spent 13 summers in Katmai National Park before being eaten in October 2003 and magically reincarnated on cinema screens. But a second, less famous grizzly man was Charlie Russell. This Canadian also “lived among the bears” from 1996 to 2004, but was generally regarded as far more sensible, and chose Russia’s Kamchatka peninsula as his domain rather than Alaska.

Charlie Russell was born in Alberta in 1941, and spent his formative years working on a ranch. Bears were common in the area, and his views on mankind cooperating with nature were forged from an early age, when he discovered that leaving the ranch’s naturally deceased cows for the bears to eat reduced the amount of living ones that they hunted. To Russell, this was like two magic puzzle pieces fitting together, as it also tided the hungry bears over until summer berry season. Everyone benefitted.

In 1960, his father (a well known conservationist) took him to British Columbia to film a documentary on black bears. Young Charlie noticed how they behaved far less aggressively if they left their rifles at home, thus reducing the need for guns in the first place. “I came to see them as peace-loving animals who just wanted to get along“. Russell spent the next 35 years devoted to bear conservation, and in 1994, he was dispatched by the Great Bear Foundation to Russia’s remote Kamchatka peninsula.

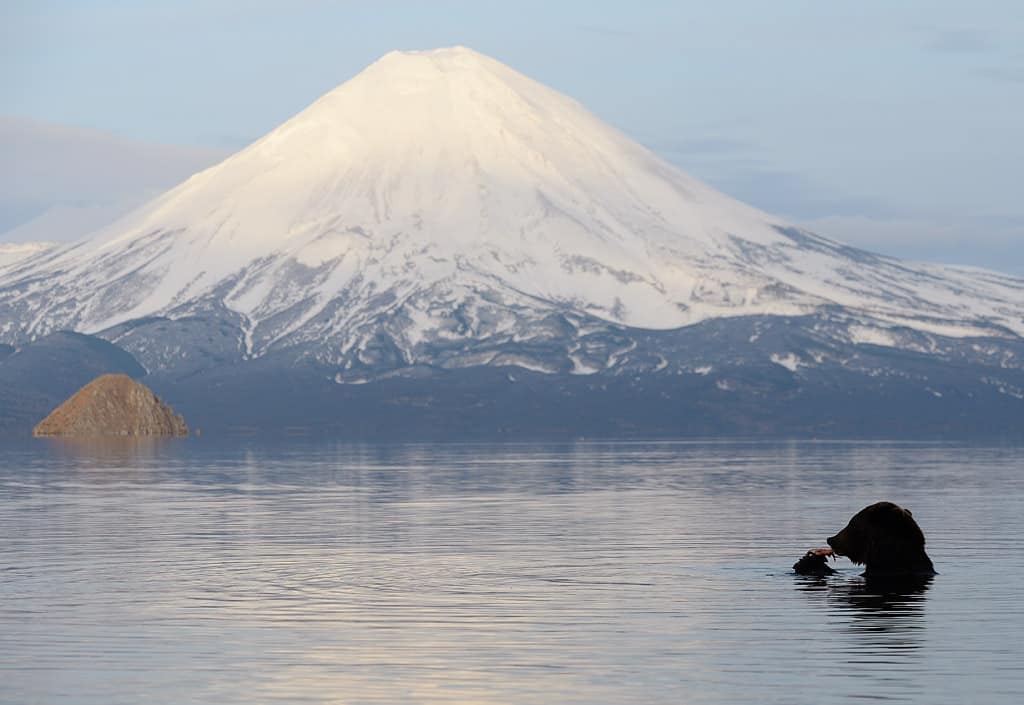

Kamchatka is a true wildlife haven, with 52 active volcanoes, one quarter of the world’s salmon stocks, and an estimated 20,000 Kamchatkan brown bears (Eurasia’s largest subspecies). Charlie’s task was to report on poaching, but from 1994 to 2007, he was drawn into an epic, ever spiralling quest.

| 2 | Russell builds a bear hut |

In 1997, Russell and his fellow bear enthusiast Maureen Enns decided to build a wooden log cabin on the shores of the remote Kambalnoye Lake. By this point, the friendlier reserve officials were calling them nashy Kanadtsy, or “our Canadians”, and in May 1997, when 3 orphaned bear cubs turned up in the squalid zoo of Yelizovo nearby, the zookeeper turned a blind eye and allowed Russell to “steal” them. He couldn’t afford to feed them anyway, so he loaded the three 15 pounds cubs into boxes for Russell, who then transported them to the cabin by helicopter and named them Chico, Rosie, and Biscuit. They were motherless bears, but Russell was determined to train them up and make them fit for the wild.

The only way to make this happen was to train them in the wild. Their training lasted for 6 years from 1997 to 2002. Russell started by taking the noisy cubs on walks around Kambalnoye Lake, where their keen sense of smell led to them to investigate everything. The cubs loved the sweet taste of the flowers growing on the tundra, and first “incident” was when they developed a taste for the rhododendrons outside Russell’s cabin and devoured them. The next lesson was fishing, which the inventive Russell achieved by placing a salmon carcass under a few inches of water. Before long, the young cubs’ natural instincts awakened, and they were diving right in, on the first step to true bear-dom.

| 3 | Russell, protector of lost bears |

By October, the three cubs weighed 150 pounds. They were becoming drowsier, but neither Charlie Russell nor Maureen Ens could stay the winter. This wasn’t a zoo. Russell was serious about preparing them for survival in the wild, like a strict and loving parent should. So instead, they dug out a makeshift hibernation shelter. This location would be a shield for them, but still give them training for the bear world.

This strict philosophy extended to playtime. The word “no” became paramount. Russell would allow no grabbings, knowing they’d be full sized bears soon. He sometimes wrestled them, but forbade this with Maureen. Sometimes, they’d use a light swat on the nose as a punishment, to mimic a mother bear’s action in the wild.

There was constant amusement with the cubs. One time, when Maureen blew her nose, the cubs fled for hundreds of metres, spooked by loud noises as most bears are. Russell said that “The cubs were so much fun to be around and the joy would just sort of seep into your own bones“. Their birch cabin had its risks, as there were bear temptations like a food box, a large compost heap, and an outhouse (which bears somehow love the scent of). Nevertheless, a flimsy electric perimeter fence with only a few wires was more than enough to keep curious adult males away. A short shop BZZZTT! sent them running. Russell discovered that the fence only needed to be knee high to work, as bears always tend to investigate objects with their nose.

Eventually, it was time to make the bears truly wild. The fencing was lifted, and they abruptly stopped feeding. “Neither of us got a wink of sleep that night,” said Russell later, but this was all part of the bear’s training program.

By 1999, their efforts were receiving international attention. Russell installed a satellite at his birch cabin, so that the whole world could receive updates using the newly formed internet. Russell’s goal was to raise money for antipoaching campaigns.

| 4 | The quest |

For decades, Russell had been convinced that bears were misunderstood creatures. He believed that they were more social than believed, that they wanted to get on with mankind, but were driven to aggression by incorrect management. His mission was to prove this principle first hand, and over in Kamchatka, one of his closest bear friends was a 5 year old female. Kambalnoye lake, which Russell’s cabin was very close to, was a fish hub where salmon went to spawn and die. There would commonly be carcasses of dead fish floating in the water, and in the years when salmon supplies were poorer, Russell would assist the female bear in her quest for fish.

Russell would spy the lake with his binoculars to locate a carcass, floating belly up, and throw a rock to indicate the location, or the general direction if it was hundreds of meters away. The female would swim towards the splash zone, and if she veered off course, she would look back and Russell would throw another rock to correct her. Then she’d return to Russell with a salmon hanging from her mouth, before the duo began their team effort anew. Russell said “it was like a dream it was so beautiful.“

Another good friend of Russell’s was Brandy the female bear. Their relationship started when she took to eating pine nuts outside their cabin and sleeping on the path leading to lake Kambalnoye. One day, she left her cubs in the care of Russell. She could sense that he was a peaceful guardian rather than a Uzi-wielding poacher, and trust was so high that over 7 years, he became the nanny to 3 of her litters.

| 5 | Russell encounters evil |

In summer 1999, Russell landed his plane by Kambalnoye lake as normal, and prepared for the joyous reunion with his cubs. But he only found Biscuit and Chico – no Rosie. Where was she? The logical explanation was predation by a male bear, and on a bench by the shores of the lake which was once a hub for playing, they found the mauled body of Rosie.

Nevertheless, Russell had always expected this bear project to have bumps in the road. He was sad, but his spirit was still strong. In 2000, Chico wandered off towards the mountains, which Russell hoped was a male bear’s natural migration to new territory. He wondered whether they’d ever see him again. Now only Biscuit remained. Ens and Russell returned every summer until 2003, and even as an adult, Biscuit would rub noses with Russell and press hand and paw together like the good old days.

Based on the way she’d spent summer 2002, Russell knew for a fact that she’d be having cubs in early 2003. Russell and Ens were overjoyed to be “grandparents”. But when they arrived in 2003, a dark chill hung over the area. There was no sign of Biscuit or her cubs. There was no sign of Brandy the mother bear, or her cubs Lime and Lemon. Something terrible had happened, and the goal was clearly to send a message to Russell. Because when they entered their cabin, they saw a sight so horrific they didn’t want to believe it – a single bear gall bladder nailed to the wooden wall.

| 6 | Russell’s anti-poaching evidence |

Ever since 1997, Russell’s Kamchatka quest had been wider than just raising orphans, and extolling man-bear cooperation. He wanted to stop Kamchatka’s epidemic of bear poaching, which started after the Soviet Union collapsed and restless soldiers returned to impoverished Kamchatka, desperate for a way to feed their families. Bears are poached for their paws and skins, but mainly the gall bladder and its bile, which Traditional Chinese Medicine recommends as a cure-all.

China has its own horrifically cruel bear farms, where a needle forcibly removes the bile, but “wild farmed” gall bladders have a higher prestige, meaning that illegal poachers can net a tidy sum. Russell was disgusted, and as he put it, “It was not fair to teach bears that people were nonthreatening if it meant that they could be killed because of their trust“.

So in 1997, Russell brought over a Kolb ultralight aircraft he had constructed himself in Canada, equipped with a 65HV engine. Flying over Kamchatka, he began to see poaching campsites and snowmobile tracks everywhere, leading towards known bear hotspots. One time, Russell saw a large male bear with its paw trapped in a metallic poaching trap. It howled and bellowed for days, and Russell wished that he had carried a gun to put the bear out of its misery.

| 7 | Russell blows the lid off |

Russell even contemplated shooting the poachers himself, but he had better ideas. His greatest anti-poaching coup came in August 1997, when Russell and his close ranger friend Igor Revenko were flying the Kolb, and noticed a Soviet Military ATV ploughing up a hillside. Russell had the guts to swoop the Kolb closer, and when Revenko whipped his camera out, the footage later showed 20 Russian poachers, one of whom was Valery Golovin, the director of South Kamchatka Wildlife Sanctuary!

Surprisingly, Golovin was prosecuted in winter 1997. His main argument was insanity, claiming that he’d experienced the longest blackout in human history: “I can’t imagine how all this happened“, he said. The judge wasn’t convinced, and Golovin was stripped of his posts and fined $9.3 million. Even his immediate boss Sergei Alekseev was fired.

To Russell, this was a beaming source of pride – a real, concrete victory against the dark forces of poaching. In 1999, he cobbled together grants from environmentalists and hired 4 of his own rangers to protect the miles surrounding Kurilskoye Lake, building them a special cabin. Unfortunately, they proved ineffective, and so Russell turned to two Russian special forces operatives returning from the blood-soaked invasion of Chechnya. Starting in 2000, they arrested a spree of caviar poachers (using their skills for good now). In Kamchatka, salmon poaching is an even worse problem then bear poaching. The peninsula is home to 25% of the world’s spawning salmon, but poachers make 10 times the salary of legal fishing employees. Most hunting is for caviar, which sells for $20 a kilo. The poachers gut the fish, rip out the eggs, and throw the carcasses back into the water, but Russell was dealing them a mighty blow.

It was another concrete success, but in the post Soviet era of oligarchs and elites, Russell’s persistence had angered someone, somewhere.

| 8 | Perseveres against the odds |

Russell’s troubles began when the tax police announced that he was flying an illegal aircraft in the country. The FSB, the secret police successor to the KGB, was also involved. They claimed that he was flying in a border zone of military importance, and before long, the tabloids were heckling Russell as a good-for-nothing American spy (he was actually Canadian). It ended with his plane’s confiscation in 2003, and that was the year when Russell and Ens returned to find a gall bladder nailed to the wall.

Later investigations confirmed their worst fears: 40 dead brown bears were found nearby, including old friends like Brandy. It was a massacre, but worse, it made no economic sense. By 2003, poaching was so common that the market was flooded with gall bladders. The price had fallen from roughly $1800 per bladder to just $60-$90, yet landing marks proved that the poachers had used a helicopter costing $1200 an hour to pilot. It was a message, pure and simple, a warning not to tamper with the shadowy economic interests of unnamed Russians. Poaching didn’t just benefit the poachers – it benefitted the middlemen of the supply chain. Two former rangers were overheard saying “The Canadians got what they deserved”.

As the freshest snow melted, Russell noticed footprints in the older layer of snow by his cabin. He also found garbage bags and shotgun shells – the poachers had used his cabin as a base. His worst fear was that the bears who he had taught to be friendly to humans had become overly trusting of the poachers who had shot them.

There was one consolation for Russell: after triggering a storm of media interest that couldn’t be ignored, the Russian authorities arrested a group of poachers responsible in December 2003.

| 9 | Retirement: the wise bear man |

In 2004, the heartbroken Russell faced a dilemma. His family was gone, but Kamchatka’s bears had been his mission for the last 10 years. While Maureen Enns decided to move on, and ended their relationship, Russell decided to return: “I will not give in, no matter what happens“. His new focus was on continuing the ranger program he had started, and developing the not-for-profit Kamchatka Bear Fund. And there was a nice bonus: he won his Kolb aircraft back!

In 2005, Russell returned to father 5 more orphaned cubs. In 2006, a BBC documentary called Bear Man Of Kamchatka was released, but by 2007, funding had finally dried up. It cost a lot to fly over Kamchatka constantly and operate the ranch. Plus, he was now 65, and his health wasn’t what it was. He retired to Alberta, Canada, but his quest wasn’t over. He was determined to change people’s views on bears. One time in 2017, he was kayaking in a river near his house, when he heard a cry of “bear”.

A bear had ransacked a picnic table looking for food, sending people scampering to a car, but when Russell calmly told the bear “no”, in a tone of voice honed by years of bear experience, the bear left peacefully. Russell then spoke to a tearful female ranger who told him that they’d shot a bear the previous day in nearly identical circumstances. He told her to get used to it: “You’re going to have to kill a lot more bears if you keep managing them this way“. She admitted they’d have to listen to him.

Still, Russell was disappointed that he hadn’t changed people’s wider bear attitudes. Ultimately, he died at the age of 76, not from the jaws of a predator bear like Treadwell, but in hospital, from complications during surgery, in May 2018.

| 10 | Relationship with Timothy Treadwell |

The two shared many interests in common, so it’s not surprising that Charlie Russell got to know Timothy Treadwell, the original grizzly man. The two often had long conversations, but Charlie Russell was under no illusions, and warned his friend regularly to be more careful. Russell himself wasn’t a naïve idealist. An electric fence was installed around the birch cabin to keep out hungry predator bears, and Russell always carried bear spray, even firing it on aggressive adult males a handful of times. Treadwell refused to do so as a matter of principal, stating resolutely that he was in the bear’s domain, not man’s.

In 2003, a few months before Treadwell’s death, Russell’s temper finally boiled over on the phone. He warned that Treadwell’s carelessness could undermine the very cause he cared about, that should he be mauled or eaten one day, the resulting media frenzy would paint brown bears as marauding killers all over again. Hunters would see them as a fair game, like in the bad old days of regional extinctions.

When Treadwell was killed by Kaflia Bay in October 2003, Russell happened to be close enough to fly out there. He later said that “I’ve seen bears like the one that killed Timothy. But I was able to stay away from them“. He argued that adoring terms like “bear whisperer” had caused Treadwell to fall into naivety over the years. His predictions for the wider movement came true when Werner Herzog’s documentary portrayed the Treadwell as a psychologically unstable lunatic. Nevertheless, Russell sympathised with Treadwell, and understood his passion for bear-human cooperation.

Leave a Reply