| 1 | The only African bear species |

Brown bears are generally creatures of the mild and cold, so it’s not surprising that 9 of the officially recognised subspecies live in Eurasia, with another 7 roaming North America. The atlas bear, however, was the only brown bear subspecies to inhabit the vast continent of Africa.

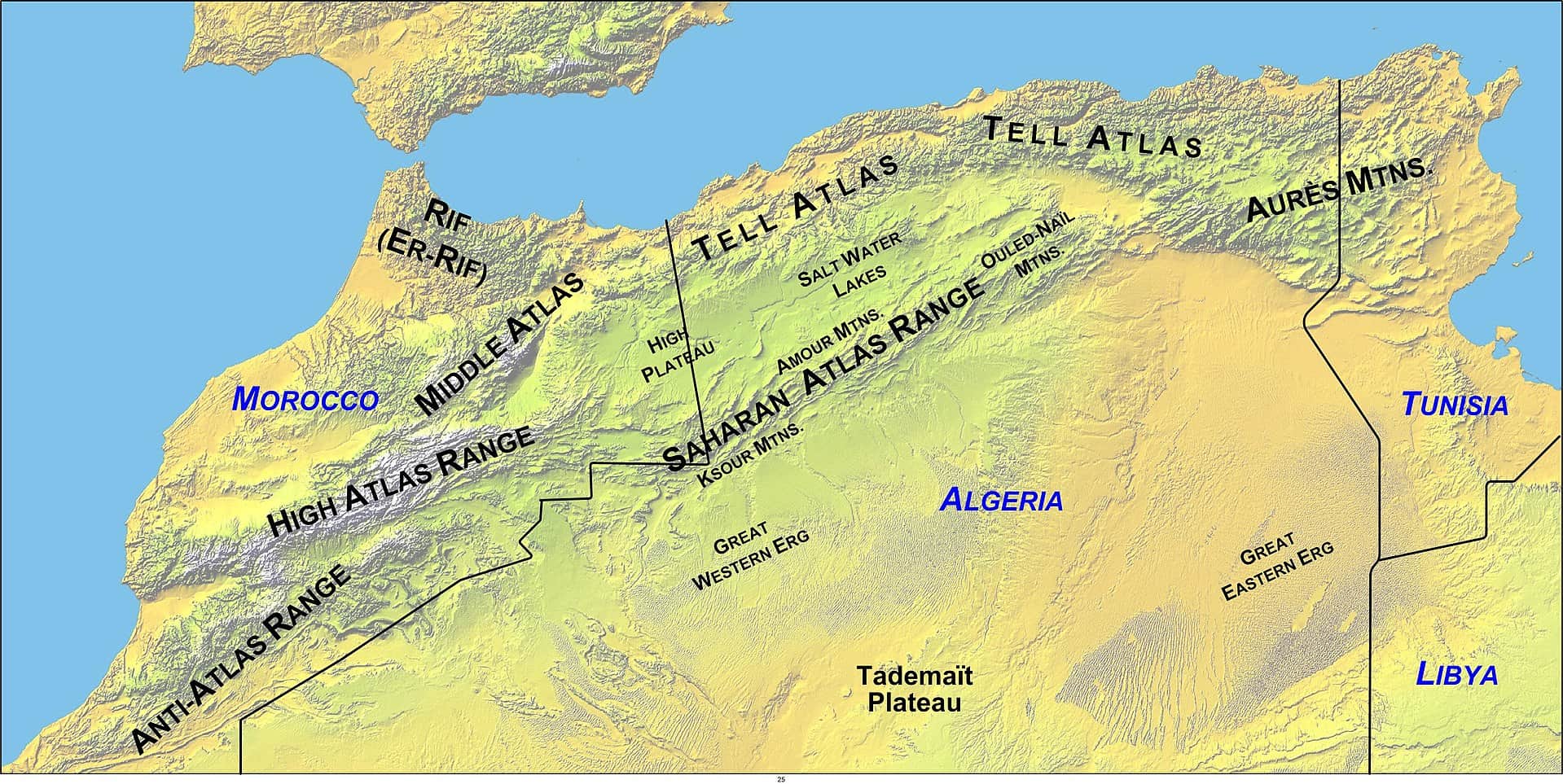

Its heartland was the namesake Atlas mountains, where it lived alongside Barbary lions (also extinct), leopards, and wild boar. These mountains have a reputation of being dusty and desolate, but the habitat isn’t too terrible for bears: there’s open forests, fast flowing mountain streams, and wild deer aplenty. Mount Tobka, for example, reaches heights of 4165 metres (the range’s highest peak), and Algeria even has a couple of rudimentary ski resorts.

That said, the Atlas bear’s heartlands also included the lowlands of Libya, Tunisia and Algeria. During colder historical periods, its range may have extended into western Egypt, but as far as historians know, the Atlas bear was confined solely to north Africa. They were forever blocked from migrating southwards by the bone-dry Sahara desert, a massive and impenetrable obstacle.

The only other confirmed bears to inhabit Africa were Syrian brown bears which occasionally strayed over the border into Egypt, unless of course, there’s a camouflaged bear hiding in the Congo rainforest which nobody has ever noticed.

| 2 | Extinct since the 1800s |

Unfortunately, the Atlas bear is long gone, without even a Tasmanian tiger-style rumour to save them. Its story was a close parallel of the much-loved barbary lion, AKA the atlas lion, a North African subspecies famed for its massive black mane that extended halfway down its belly. This lion went extinct in the early 1900s, and the atlas bear died out slightly earlier, with the official date being 1870.

The Romans are most commonly blamed, by kidnapping them for gruesome battles in colosseums, but the Roman empire ended in 476AD. Instead, the main culprit was massive overhunting by the local Berber tribes, whose orchards were constantly pillaged by the bears. Sightings were plentiful until 1850, but no hard evidence such as pelts, fur or droppings was discovered throughout the entire 20th century.

In fact, not only is the atlas bear extinct, but no pelts or fur were ever preserved for analysis. Strangely, not a single piece of atlas bear remains can be found in a museum.

Despite having gone extinct over 25,000 years later, the atlas bear is significantly less researched than the prehistoric cave bear. With the barbary lion, we have some stunning black and white photographs of it sitting on rocks with its majestic mane, but no photographs of the atlas bear are known to exist. Scientists never conducted any serious expeditions to watch atlas bears in motion, to analyse their diets, sleeping patterns or interactions with humans.

| 3 | Appearance of the Atlas bear |

Despite the lack of photographs, the Romans encountered atlas bears so constantly that we still have a decent idea of their appearance. According to legend, the subspecies was particularly stocky, but their height and weight ranked close to last for brown bears, though with a disproportionately large head. The females were said to be even smaller than American black bears. The fur was the standard brown/black, but with hints of red on its underbelly, unlike the near-yellow Syrian brown bear or the Tibetan blue bear. Their diet, meanwhile, consisted of nuts, acorns and roots, but while atlas bears tended to be herbivorous, they weren’t averse to eating small mammals such as crillion.

According to stories from local Arabs in the 19th century, the atlas bear was particularly fond of honey. The Atlas bear would climb up a tree with nimble skill, break open the bark and remove the hive, before gorging on the honey until full. Then the local Arabs would scrape out the wax which the bear had ignored and take any remaining honey globules. Another recollection was that Atlas bears stood up on their hind legs to fight people.

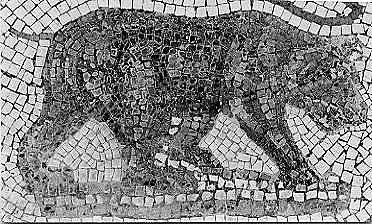

The claws and muzzle were slightly shorter than usual, and the Romans reported that atlas bears had the longest coats of all bears, with each hair being 10-12 centimetres long. However, ancient mosaics clearly show that the Atlas bear had all the classic brown bear features – a hump, an upturned concave nose, and small, rounded ears.

| 4 | Fought in Roman colosseums |

As the Roman empire steamrollered through North Africa, they picked up all sorts of wild animals, including bears, with an eye on their spectacular colosseum battles. Roman warlords engaged in no less than 33 enationes bestiarum africanarum (African animal hunts) during the mighty reign of Augustus, as an all-out celebration of their mighty conquests. No less than 3500 wild animals were slaughtered during these gruesome bloodbaths. Emperors Titan and Traja butchered 9000 and 11,000 animals apiece, the latter to celebrate his conquest of Dacia in 101AD.

You’d almost admire Emperor Commodus if he wasn’t so bloodthirsty; he personally managed to kill 100 “Numidian bears” in the arenas during his lifetime, as reenacted by the 1964 epic The Fall Of The Roman Empire. This was supplemented with a rhinoceros, a tiger, a giraffe, ostriches, 6 hippos, and 3 elephants, which demonstrates how bears were overwhelmingly the favourite opponent. Commodus’ weapons of choice were scythe-shaped arrows which he fired into their necks. During his gladiatorial career, a magistrate called Domitius Ahénobarbus supposedly fought against 100 Numidian bears and 100 Ethiopian tribesman (not what we’d expect from a magistrate today), as relayed in a text by the famous Pliny the Elder.

Another trick was releasing prisoners into the bear enclosure to execute them. To make the bears aggressive enough for these gladiatorial battles, the Romans would starve them, to induce a state of wild desperation. Something tells me that Greenpeace wouldn’t approve of this today.

| 5 | How they reached Africa is unknown |

One major mystery about the atlas bear is how they ended up in the arid mountains of Algeria and Morocco in the first place. The nearest species geographically are the Iberian brown bear of the Spanish Pyrenees and the light-coloured Syrian brown bear roaming Iraq and Syria.

The instant explanation would be an ice age land bridge forming between Gibraltar and Morocco. At its narrowest point, the strait is only 7 miles across, but unlike the English channel (the now sunken Dogerland), the ocean there is extremely deep, and it’s believed that no land bridge has ever formed.

Instead, the first possibility is that the Syrian brown bear gradually migrated westwards, during cooler times when the Mediterranean coast was luscious and more able to sustain life. Afterwards, as dust and desert reclaimed north Africa, the inbetween bears in Egypt and eastern Libya would have died off, leaving the separated western pocket free to evolve into the atlas bear subspecies. The final possibility, of course, is that some absolute maniacs of European bears swam across the strait in one mammoth effort, being only 7 miles wide and all.

One old theory is that Atlas bears were never native to Africa, but were actually feral European bears, brought over by conquering Romans and Carthagians, and later escaping from battle arenas. However, this theory is completely disproven by ancient bear skeletons discovered in the Takouatz cave in Algeria, which dated back to 7000BC, predating the arrival of Romans by eons.

| 6 | Some believe they never existed |

Over the last 200 years, the Atlas bear has had a strangely high number of doubters, with some categorising it alongside the Yeti or sasquatch. Some scholars have argued that the Roman colosseum bears were simply European bears. A significant proportion undoubtedly were, but in the old Roman literature, an extremely common term is “Numidian bear”. For example “The bears of Numidia prevail over the rest, but only in fury and in the length of their coat“.

Numidia refers to the empire of North Africa spanning Algeria, Tunisia, and western Libya, the precise range of the Atlas bear. Even the description of a long coat matches the reports of 19th century Arab tribes. Later in 800AD, crown prince Charlemagne was offered a “Numidian bear” for the ceremony before his coronation, by Ibrahim ben-Aglad, the emir of present day Tunisia.

Also, Roman historian Dio Cassius described how a gladiator called Publius Servilius “caused the killing at a spectacle of three hundred bears and other African wild beasts in equal numbers”.

The Atlas bear’s existence was still doubted as late as 1932, by mammologist Angel Cabrera, and even in 1991, by Kazimierz Kowalski and Barbara Kowalska-Rzebik. By 1998 however, archaeologists had carbon dated a small bear bone from a cave in the Algerian Djurdjura back to 440-600BC. In 2007, yet more bear bones were discovered, this time in Morocco, and dated back to 778AD.

| 7 | Local Berber tales |

If there’s any doubt remaining over the Atlas bear’s existence, then the first hand accounts of Berber locals quash them completely. As the French colonised Algeria in the 19th century, several naturalists were sent to document the local wildlife, with the most productive of all being Jules-René Bourguignat. In 1870, an Algerian tribesmen informed Bourguignat that back in 1845, his friend had shot a bear, and pursued it for miles without dealing the finishing blow.

Over in Libya, a boastful member of the Ouled-Orab tribe claimed to have killed approximately 30 bears in 1830, while a member of the same tribe claimed to have injured a bear on the slopes of Jebel-Ghdir near Benghazi. Several Berbers gave Bourguignat first hand information on the bear’s love of honey, and tendency to fight while standing on its hind legs.

Even geographical names confirm the existence of bears in historical times. A ravine called Chabet-el-Dèb lies near the town of Cirta in Algeria, which translates loosely to “bear ravine”. Between the Algerian towns of Bône and Guelman, a spot exists called Guelaat-el-Dèbba (stronghold of the bear), and close to the Algerian town of Jemmapes lies a river called Oued-el-Deb (bear river).

| 8 | Frenchman finds a bone |

Bourguignat himself had several hair-raising encounters with Atlas bears, which fell just short of witnessing one in the flesh. In 1867, in a cave near Jebel Thaya in the Constantine region of Algeria, Bourguignat unearthed some fossilised bones, including 3 bear mandibles, which appeared to be from a whole new species. Sitting alongside them was a lamp whose style clearly dated back to the 6th century AD, proving at the bare minimum that bears had been around in the historic era.

The bones belonged to a relatively small bear, which was “stocky, tightly packed and short on legs“, with a “relatively large head, not very elongated, terminated in a very narrow muzzle“. Bourguignat believed that he’d discovered an entirely new species, and in a letter, he communicated his findings with a Mr Letourneux back in France, a seasoned imperial officer.

In response, Letourneux revealed that during his long career stationed in Algeria, the Arabs of Edough told him that bears were plentiful in the area, and routinely devastated the vines of their orchards. 50 years earlier, an Arab had told Letourneux that one of the last bears in the country had been slayed by his father.

| 9 | Frenchman finds a skeleton |

In 1870, the quite obviously bear-obsessed Bourguignat had an even more vivid encounter: a fresh bear footprint, which he estimated to be no more than 3 hours old, judging by its impeccable imprint in the mud.

The footprint was so fresh that the water squeezed from the earth by its pressure was still resting on the banks of mud on either side. The print was obviously too deep to have been created by a human. Bourguignat was exploring the cave with several Arab associates, and when they first witnessed the footprint, they exclaimed “dèb, dèb“, the local dialect for bear.

On a separate expedition, Bourguignat discovered fresh bear bones, which a doctor friend deemed to be no more than 15 years old. He also received reports from two Arabs called Ben-Djemil and Ben-Aoun living in the town of Edough who insisted that until only recently, a top priority of there’s had been defending their orchards against marauding bears, confirming the rumours that old man Leternoux had relayed.

In his writings, Bourguignat commented on another local saying: “The work of the bear makes the bee hunter happy“. This referred to the atlas bear’s habit mentioned by other Arabs, of removing a beehive from a tree, scooping out the insides, and leaving it behind for the locals to finish off.

Doctor Victor Reboud was another experienced atlas bear investigator, having visited Algeria on an archaeological trek in 1875. He noted several more suggestive local expressions, including “rude as a bear” and “he growls like a bear”.

| 10 | The end of the atlas bear |

The accepted theory today is that the last ever Atlas bear was shot dead in the Tétouan mountains of Morocco’s far north, back in 1870. Yet the Atlas bear’s range was always vast, covering Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria and Libya. What are the chances that the last ever north African bear happened to stray into the arms of human hunters?

The population undoubtedly plummeted during the 1800s. For example, an Englishman called Alfred Pease who lived in Algeria from 1892 to 1896 reported that while rumours of bears were still in overdrive, concrete sightings were a thing of the past. From 1850-1900, French colonialists explored Algeria in massive detail, naming whole new valleys and peaks, and bear encounters were still almost non-existent. Yet nobody is omnipotent.

As late as 2005, a student called Dady Seter interviewed locals in the Djurdjura massif and Akfadou forest regions of Algeria, and was informed of 5 bear sightings dating from 1940-1950. In the village of Ifigha, he showed an elderly woman some clear photographs of bears, and suddenly, she started to relay an ancient story. During the Algerian revolution, which started on November 1st 1954, the woman and several friends were working in an olive field, when a mother bear with two cubs approached from the wild. The group only survived by climbing a tree and waiting patiently until the bears left.

Could this have been a real atlas bear, perhaps one of the last 50 or even 20 survivors? It’s unlikely, but no other animals resembling a brown bear are native to North Africa.

The overwhelming likelihood is that pockets of Atlas bears survived for several more years after 1870, and quite possibly into the early 20th century.

Leave a Reply