The best known bear film of recent years is undoubtedly The Revenant (2015), which claims to be based off the true story of 1820s fur trapper Hugh Glass, played by Leonardo DiCaprio. Anyone who has heard of this film will know that it features a gruesome scene where DiCaprio is mauled by the best trained CGI grizzly bear of all time. His injuries are so severe that his fur trapper colleagues leave him for dead, forcing DiCaprio to crawl across 200 miles of American wilderness and seek bloody revenge.

The shoot was gruelling, with director Alejandro Iñárritu refusing to use green screen for location shots and instead marching the entire crew out into temperatures of -25C for weeks. To get into part, Leonardo DiCaprio claims to have eaten raw bison liver and slept inside an animal carcass. It paid off, as he finally won his first Oscar for best lead actor. But how much of the story is accurate, and what about the bear sections specifically?

The film invented several details such as Hugh Glass having a half Pawnee son, from a marriage to a Native American. In reality, he probably had no children. One almost guaranteed myth is a second grizzly bear arriving and licking the maggots from Glass’ open wounds, probably caused by the story changing hands too many times over the centuries. There are almost no written records, but here’s the real story as best we know it…

| 1 | The expedition begins |

The early life of Hugh Glass is almost a complete mystery. Compared to Grizzly Adams, for example, we don’t even know where Hugh Glass was born, with two popular theories being Scotland and Philadelphia – perhaps both at some point on the timeline. Crazy tales also exist that Hugh Glass spent two years as the captive of notorious pirate Jean Lafitte. He supposedly escaped by jumping ship near Galveston, Texas and swimming to shore, after which he fell into the clutches of the Pawnee tribe. He only escaped being burnt alive when he offered the village elder a handful of vermilion, after which the Pawnees taught him every fur trapper skill he knew.

The official story starts when Hugh Glass signs up to the St Louis hunting company in 1823, run by William Henry Ashley and Major Andrew Henry. In May, he left on an expedition set to last the entire summer, led by Major Henry and starting with 27 men.

At nearly 40 or just over 40, Glass was among the oldest trappers, and had mild loner tendencies, often walking by himself. However, he was respected as wise and experienced by his fellows, such as 19 year old Jim Bridger, who was only on his second trapping season. Two slightly older fur trappers were John S. Fitzgerald and Moses Harris. The party sailed down the Missouri river searching for valuable beaver streams, but the year was 1823, and Glass knew that they were sailing into a lion’s den of ever-spiralling Native American warfare.

| 2 | Waves of Native assaults |

The first trouble for Glass’ company came on June 2nd. As they sailed down the Missouri river, a war party of Arikara (also known as Ree) attacked and killed 17 of their party, forcing them from their boats. Glass himself took a nasty shot to the thigh. As the dying men were nursed back to health, Glass focussed on young John Gardner, who relayed his dying wishes to him.

In one of the few pieces of writing ever discovered by Glass, he wrote a letter to Gardner’s parents, starting by saying “My painful duty it is to tell you of the deth of y[ou]r son” and finishing with “a young man of our company made a powerful prayer wh[ich] moved us all greatly and I am persuaded John died in peace…’. The articulate letter proved that Glass was literate and was educated somewhere in his murky past.

From then on, it was constant vigilance. Friendly tribes like the Mandans appeared to be turning against the Europeans, and one night these warriors slaughtered two more of the party. Major Henry cursed that US army forces had promised to punish the Arikara for the June 2nd attack, but done nothing about it. Glass and his trapper party were forced to avoid the river and march through the wild Grand River valley. Major Henry ordered the party to stay in tight formation and only allowed 2 hunters to leave the pack at once. One fateful night in mid August, it was Hugh Glass’ turn.

| 3 | The bear |

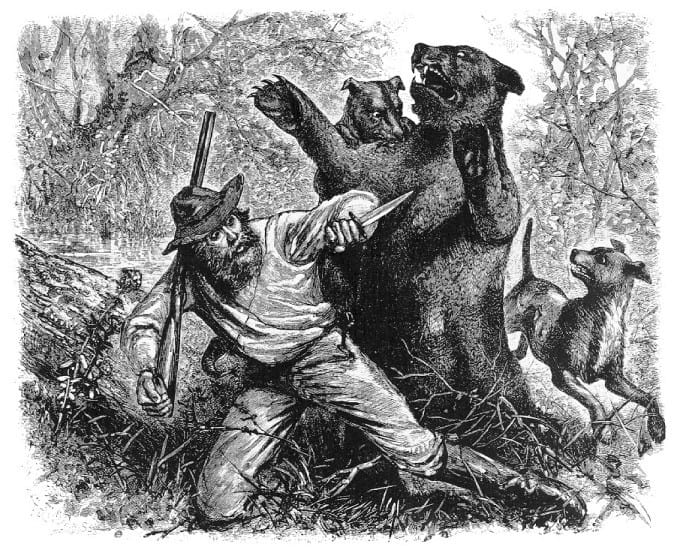

Precisely what happened during the legendary bear attack is a mystery. Whether Glass fought back, played dead, tried to climb a tree or called for help will never be known. Glass might have been jumped from the undergrowth, or he might have stayed calm for the first minute only to suddenly be charged from 20 metres away. Nevertheless, the common story is that he stumbled upon a mother with cubs, a she-grizzly with 3 inch claws. After a life or death struggle, the bear was felled with one bullet, then two, and then a dozen.

When Major Henry and company dragged Glass clear, he was a ragged and torn mess of a man. He throat was torn at the centre, and with each choking breath Glass took, a bubble of blood would grow and pop. Everything was shredded, his chest, his face, his arm, his scalp. He couldn’t stand. They had no idea that an epic story of survival which would echo through the centuries was beginning before their very eyes.

Glass was alive, but for how much longer? At first, Major Henry and company tried to help Glass. They tore strips from their clothing, bandaged his wounds, and settled down to sleep, assuming Glass would be dead in the morning. But when the sun rose, he was still kicking. So they crafted a makeshift stretcher out of branches and carried Glass for 2 days, covering only minimal distance, a story which could probably cover pages if only we had more details.

| 4 | Glass edges towards death |

At the fork of the Grand River in modern day South Dakota, under a canopy of grove trees near a small stream, Major Henry decided that it was time to face the facts. They were smack bang in the heart of Indian country and Glass was fading in and out of consciousness. He was a feverish wreck and if they maintained their sluggish pace, Henry would probably lose more men to arrows. He announced to the trappers that they would leave Glass by the stream, so that he could recover and follow under his own power, but the implication was grim: they were leaving him for dead.

Henry then made a tantalising promise: a hefty financial bonus for anyone who would stay and bury Glass according to Christian traditions, equivalent to several months of wages. Allen and Moses Harris had no desire to sit around in Arikawa country singing songs, but younger John Bridger, with a sister to support, reluctantly volunteered, as did John G Fitzgerald.

As Major Henry and company faded into the distance, shrinking into dots, Fitzgerald looked at his quarry. Glass was wheezing, flicking in and out of consciousness, clinging to life. The duo slept for two nights, but to Fitzgerald’s dismay, Glass was sure taking his time about dying. If watches were invented in 1823, then Fitzgerald would have been checking his every minute. Every hour, catching up with Major Henry would become harder. More bears could be out there prowling, hungry for flesh. That was when the betrayal happened.

| 5 | The abandonment |

As the pale Hugh Glass lay with a cold sweat on his forehead, surrounded by flies, Fitzgerald turned to Bridger and suggested that his death was inevitable and that they might as well leave now. The younger, more compassionate Bridger was reluctant, but saw sense after Fitzgerald dangled the threat of Indian night raids over his head. The fear of the unknown was too strong, but the duo had a problem. They’d been left with strict instructions to afford Glass a proper Christian burial, and consequently, their precious bonuses were at stake. All evidence had to be cleared, and Fitzgerald cleverly reasoned that a dead man would never be buried with his valuable equipment in the Grand River wildlands.

And so, as Hugh Glass lay half-dead, in a feverish dream world, Fitzgerald and the reluctant Bridger stripped him of everything he had. Glass’ protectors took his knife, his flint, his steel, his powder, leaving only his blood-stained clothes. To add insult to injury, Fitzgerald picked up Glass’ trusted rifle, a prized possession of his, eyeing it with admiration.

The duo moved the soon-to-be corpse to within touching distance of drinking water. With a last glance back, Fitzgerald and Bridger abandoned Glass to the wilderness. What they didn’t notice was the spark of undying determination and survival in the man’s eye.

| 6 | Glass becomes a survival machine |

Somehow, as fever raged and blood poured from his wounds, Glass’s warped mind registered what had happened. He summoned up hidden reserves of energy from deep inside himself, and continued to cling to life. Driven purely by will and the sense of ultimate betrayal, his first move was to tentatively grab some buffaloberries from a bush, and force them down his mangled throat with the help of water.

His next opportunity came when a rattlesnake slithered past, which Glass quickly hunted with a clubbing from a nearby rock. He skinned the serpent and divided the meat into thin enough slices to swallow. Slowly, the lucid moments began to outweigh the dream-like fog, and Glass realised that he had to get moving. He stood up, and fell back down again. His legs were crippled. So Glass crawled, using his one good arm and one good leg. He followed the river downstream, aiming for the lofty goal of Fort Kiowa, a French fur post. At first, one yard felt like an accomplishment, before his body conked out. But Glass couldn’t die – he had to get his rifle back first.

Like a zombie bite victim, Glass slowly became more like a bear himself. When he crawled upon a buffalo carcass, he cracked open the bones to eat the sweet marrow inside. He stole eggs from birds nests, and hid in the bushes while a wolf pack circled and hunted a calf. Waiting for his opportunity, he flushed the barking wolves away and scavenged the heart, guts and liver which they had ignored.

| 7 | Progress at all costs |

Glass was getting stronger, but the fur post was 250 miles away. Meanwhile, the savage wounds on his back were now infested with maggots (and a bear didn’t turn up and lick it clean). Yet his legs were stronger, and one day, Glass proudly rose to his feet again. He was through the worst, but for all he knew, another bear mauling or scalping by Indians was in his future. The sense of betrayal burned. Fitzgerald was out there somewhere.

Glass next had a stroke of luck, meeting a group of Sioux by the Missouri river who took pity on him. The friendly natives cleaned his back wound, and soon, Glass had triumphantly reached his goal of Fort Sioux. There he met a rival French hunting party which was heading to the Mandan villages to re-establish a trade route.

Unbelievably, the half-dead Glass signed up. He was handed a new rifle, which was nice and all, but deep down, he wanted his old rifle back, and he knew where it was. The French were headed close to Fort Henry, the ultimate goal of Major Henry’s company, so Glass opted to tag along. Yet in mid-October 1923, only two men stepped off the boat and reached the friendly Mandan villages: interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau and Hugh Glass, the ultimate survivor. A murderous Arika party had massacred the rest, while Glass was ashore on a mini hunting sirjoin and Charbonneau explored further ahead.

| 8 | Fort Henry |

Call it luck, call it finely honed instinct, but these waves of Indian assaults were only a distraction for Glass. After trudging along the Missouri river’s banks for dozens of miles, Fort Henry finally came into sight. Glass tasted revenge, but after crossing to the opposite shore using a makeshift raft of two logs tied together, he found the doors shut, the rooms cold and the beds empty. Glass discovered clues suggesting that Major Henry had travelled south down the Yellowstone river, and off he went again.

It wasn’t until January 1824 that Glass finally caught up with Major Henry and company. He had travelled over 1000 miles when he marched his bear-torn, corpse-like body into the gates of an all-new fur trappers’ fort. There he discovered his former colleagues celebrating the new year in style and comfort, far away from the rugged world of death that Glass had just ground his way through.

At first, their eyes popped out of their sockets, but when Hugh Glass identified himself, disbelief turned to rapturous celebration and a thousand questions. Yet one man’s expression became progressively darker – 19 year old Jim Bridger. As the other men realised the implication of what the stony-faced Glass was saying, their moods darkened as well. Bridger seemed so ashamed that Glass’ months old thoughts of blasting his head off with a rifle were forgotten. He was young, and Glass decided to forgive him, but Fitzgerald was another story.

| 9 | The grand finale |

A final showdown beckoned, but to Glass’ dismay, the clever, rifle-snatching John G Fitzgerald was nowhere to be seen. Major Henry explained that Glass’ abandoner had enlisted in the army and had left the party in mid-November alongside Moses Harris. The next revelation was a real punch to the gut – Fitzgerald had sailed south down the Missouri river just as Glass had been sailing in the opposite direction.

After a period of recovery, Glass set out for Fort Atkinson on February 28th, teaming up with two trappers called Dutton and Marsh. On the way, he met up with “friendly” Pawnee Indians and set down in their tent, but Glass noticed a glint in the man’s eye. These weren’t Pawnees, they were Rickarees! Glass bellowed a warning, and only just escaped to a rocky sanctuary while his companions Moore and Chapman were slaughtered.

Dutton and Marsh reached Fort Atkinson and reported Glass’ demise, but in early June 1824, Glass finally arrived and proved every man and his dog wrong yet again.

Finally, the story ends, but it ended with a whimper. As predicted, Fitzgerald was at Fort Atkinson. Despite the sympathies of the local troops, who donated a fund to him, the US army wouldn’t allow Hugh Glass to shoot one of its soldiers dead. Glass never got the confrontation he wanted, but settled for the return of his trusty rifle and a dirty black mark on his betrayer’s reputation. His 10 month odyssey was finally over.

| 10 | The aftermath |

By 1825, the legend of Hugh Glass had already taken on a life of its own, and a largely fictionalised column of his adventures had appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Glass himself, meanwhile, continued to work as a hunter by the mouth of the Yellowstone River as an employee of Fort Union, as proven by several surviving paper business records.

In 1833, he and two other trappers were crossing the iced-up Yellowstone river when a war party of 30 Arikaras charged and surrounded them. There were no trees to climb, no deer paths to slip away into, and this time Glass was unable to escape his doom. The triumphant Indians rode away with Glass’ cherished rifle and his death was soon reported in The Milwaukee Journal. Even these details are slightly blurry, as they were merely relayed by a fellow employee stationed at Fort Union.

Glass’ luck had finally run out, but he had lived for an extra 9 years since Fitzgerald and Bridgers had left him to die. Not bad for a guy whose back was temporarily the home of a family of maggots. One of the biggest differences was that Glass’ real story took place in summer, and not winter as the icy blizzards of The Revenant suggest. Fitzgerald was made into an even nastier villain by murdering Glass’ non-existent son, and one facepalming detail was Fitzgerald leaving to enlist in the Texas rangers. Small problem – Texas wasn’t part of the US yet!

Leave a Reply