| 1 | Once roamed all of Europe |

It’s no secret that the cave bear is a legendary, extinct animal, which was an everpresent part of ancient cavemen’s lives. The dates are far from nailed down, but the cave bear probably lived from around 1 million years ago to 24,000 years ago. The extinction was later than the Neanderthals, but significantly earlier than the woolly rhinos (12,000 years ago) or the woolly mammoth, whose last fragmented populations died only 4,000 years ago on Wrangel Island.

Both brown bears and cave bears are thought to have had the same common ancestor: the Plio-Pleistocene Etruscan bear (Ursus etruscus), which lived from 5.2MYA to 80,000 years ago, and was slightly smaller than modern bears. It’s estimated that the two diverged 1.2-1.4 million years ago, well before polar bears split off. The cave bear lived all over Europe, from the modern day British Isles, to Italy and even northern Iran. However, the alps were undoubtedly its stronghold. Austria, Switzerland, southern France and northern Italy have easily had the highest quantity of skeletons discovered.

Modern brown bears regularly take shelter in caves, but cave bears took it to the next level, using them as their exclusive hibernation domains. Prehistoric paintings have been discovered of cave bears, yet there were far more of regular brown bears, showing just how much time they spent huddled away in remote cave passages.

| 2 | Big yet shy |

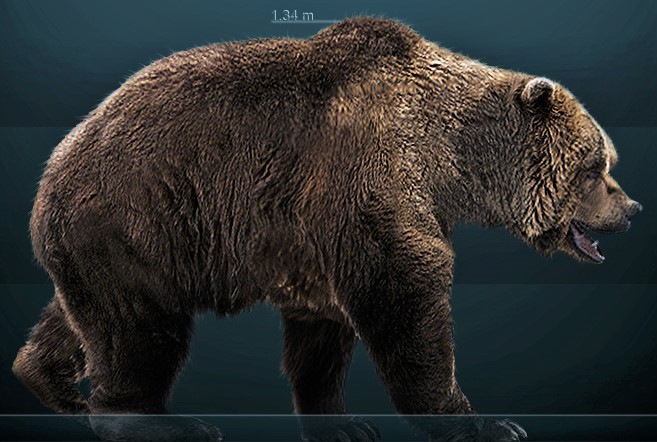

Cave bears were a gigantic species. Males averaged at 1000 pounds compared to 600 pounds for the modern grizzly. The classic image of a ferocious cave bear on its hind legs looming over a cavemen crowd was very much real. However, at 500 pounds, females were way smaller, so small that they were misidentified as normal brown bears, or an unidentified dwarf bear species. Archaeologists spent years wondering why they could only find male cave bear skeletons. Today, 90% of museum specimens are male.

The cave bear is believed to have been relatively herbivorous. We know this from the teeth found in its skeletons, which are significantly more ground down compared to modern bears, hinting at a life spent chewing on tough vegetation. Its favourite foods were believed to be nuts and acorns, but it was still able to eat meat during leaner times, particularly smaller mammals and carrion. In old cave bear bones unearthed in the Carpathian mountains of Romania, scientists have detected elevated levels of nitrogen-15, an ingenious modern method for detecting animal protein consumption in long-dead animals.

| 3 | European caves are littered with their bones |

The cave bear is probably the most frequently discovered prehistoric large mammal of all time. From the middle ages to early 1900s, hundreds of thousands were discovered in deep, dark caves all over Europe. Terrified villagers often believed them to be dragons. Imagine being a daring local lad in a 1700s Austrian village, guided down a local cave by only your lantern while your friends egged you on. Turning a cave passage, you suddenly stumble across the 200 pound skeleton, resting against a wall only half-illuminated. This is a story that legions of people would have experienced.

Cave bear skeletons were so abundant that in the latter stages of World War 1, the Germany army ground them down en masse to make phosphorous, a raw material for bombs and grenades. It’s a thought that would make archaeologists recoil in horror, but the skeletons were too many to count: new bears would occupy the same caves over the course of 1 million years (or close), leading to an exponential build up. Elderly bears would die inside the caves during hibernation, having failed to fatten up enough in the bulking season. Occasionally, cave lions and cave hyenas would sneak in and kill the infirm ones at the back. Cave lion skeletons have also been found deep within cave bear chambers, hinting that some paid for the attempt with their lives.

| 4 | Forgotten and rediscovered |

30,000 years ago, our ancestors knew exactly what cave bears were, but for the last thousand years, people didn’t have a clue.

The earliest records of European cave exploration were in the 15th century, and these already mention large bones, but instead, they were considered to be unicorn fossils, which were harvested for folk health remedies. By 1656, progress was being made: Horst theorised that giant bones in Germany’s Einhornhöhle cave (which translates to “unicorn cave”) could belong to bears, lions and humans.

How about the first pictures? They were sketched in 1673 and 1676, by Paterson Hain and Vollgnad respectively, who stuck to the familiar belief that they were the bones of dragons, living in the Carpathian caves of eastern Europe. These dragon references are everywhere in the 18th century. A 1739 text by Franz Bruchman also describes a dragon skeleton discovered in the cave of Liptovien in Hungary.

The official discovery happened in 1774, when Johann Esper published the first massively detailed diagram of a skeleton in his book Newly Discovered Zoolites of Unknown Four Footed Animals. He judged it to be a prehistoric polar bear skeleton, which wasn’t the worst guess in scientific history. Quickly though, people realised that it was much larger than any living bear species. Finally, in 1794, a Mr Rosenmueller proclaimed that the bones belonged to an extinct ice age bear, which he called ursus spalaeus, the latin name which still stands today.

| 5 | Extinction: natural reasons |

Why did cave bears go extinct? Climate change may have been a factor, as the ice ages beginning 100,000 years ago could have steadily ground them down, until the ultimate extinction 24,000 years ago. Unlike woolly mammoths and woolly rhinos, cave bears were less of a cold-loving prehistoric creature. With their herbivorous diets, a sudden retreat of plant life leaving only hardy shrubs and berries could have been a disaster, compared to the more flexible and omnivorous brown bear.

The cave bear’s larger sinuses may have been involved, cavities in the skull which hold gases like nitric oxide. In cave bears, the sinuses triggered hibernation, but they also tend to change the skull’s shape in animals, forcing the back teeth into being more developed. It’s believed that in cave bears, their front teeth became so woefully underpowered that they couldn’t switch to meat effectively during colder periods, except in small doses.

Interestingly, the skeletons across various caves in Spain and France had extremely similar DNA halotypes within each cave. It was like there were individual pools of cave bear lineages all across Europe. It’s possible that they gave birth and raised cubs entirely “at home”, which would make migrating to new areas very difficult, making cave bears a very inflexible species. Yet another theory is that the cave-bear had an unusually small brain relative to its body size, and was “stupid” compared to brown bears.

| 6 | Extinction: human interference |

Scientists currently estimate that cave bears and mankind co-existed for 20,000 years. The question is inevitable: did humanity’s arrival hasten their demise? The current theory is that cave bears were so hemmed into their narrow niche that when cavemen finally looked to caves for shelter, the consequences were disastrous. The cave bears were probably met with a volley of arrows and spears, and forced to hide out in the bitter cold, which they weren’t adapted to. The more versatile brown bear was able to hibernate in exposed areas (and still can, obviously), like thick clusters of trees, making its own dens.

Scientists currently estimate that cave bears and mankind co-existed for 20,000 years. The question is inevitable: did humanity’s arrival hasten their demise? The current theory is that cave bears were so hemmed into their narrow niche that when cavemen finally looked to caves for shelter, the consequences were disastrous. The cave bears were probably met with a volley of arrows and spears, and forced to hide out in the bitter cold, which they weren’t adapted to. The more versatile brown bear was able to hibernate in exposed areas (and still can, obviously), like thick clusters of trees, making its own dens.

The cave bear population first plummeted around 40,000 years ago, when homo sapiens started fanning out northwards and eastwards. Coincidence? Proponents point out that the cave bear population had been stable for tens of thousands of years beforehand, withstanding endless ice ages. Tribes of humans could have driven the cave bear away from its summer foraging grounds as well. It’s confirmed that cavemen hunted cave bears, thanks to flints embedded in ancient vertebrae.

The current 2022 theory is that human tribes did the initial damage, with an intensifying ice age beginning around 24,000YA performing the final “coup de grace”.

| 7 | Relationship with people |

One controversial theory is that prehistoric humans worshipped cave bears, popularised by the 1980 book The Clan Of The Cave Bear. The theory was dismissed, but in 1924, scientists evacuating Drachenloch cave in Switzerland discovered manmade stone chests. Inside were several cave bear skulls, deliberately placed. The arrangement appeared to be artistic, ritualistic. In 1920, French scientists discovered a cave later named Chauvet in the southern Ardèche region. In dim light, they stumbled onto 150 cave bear skeletons, alongside clear footprints embedded in clay. But that wasn’t all: one skull was positioned in the centre of a stone slab, in a separate chamber. There’s no proof that this was a scene of worship, but the walls were lined with cave paintings of hyenas, lions and cave bears. The occupants of Chauvet cave were dated to 32,000 years ago.

For hunting, there’s plentiful evidence. A cave called Höhle Fels in the German mountainous region of Swabian Jura contained numerous cave bear skeletons, one of which had a vertebra embedded with flints from a prehistoric spear, dating back 29,000 years. Back in 2000, this was considered to be an epic discovery.

| 8 | Extinction: date unknown |

The current consensuses is that ursus spalaeus, or the cave bear, went extinct 24,000 years ago, mainly because that’s the latest conclusively dated skeleton. A serious decline in genetic diversity started around 50,000 years ago, and by 35,000 years ago, the cave bear was seriously less common in Central Europe. Nevertheless, there isn’t a bear expert on Earth who will profess to know the exact date.

South of the alps, cave bears survived for much longer, which could be because of a warmer climate making their herbivorous foods more abundant. It also hung on in the northwest Iberian peninsula for significantly longer. Could pockets of the cave bear have survived beyond 24,000 years ago? It’s likely, but not for much longer, mainly because skeletons of cave bears are incomparably common. Tens of thousands of skeletons have been discovered in European limestone caves over the centuries. Unlike rarer Neanderthal skeletons, where new discoveries are constantly forcing scientists to revise their dates, we’d almost certainly have discovered the smoking gun for a later cave bear extinction date already. Yet nothing is inconceivable.

| 9 | The Drachenhöhle |

Throughout the medieval period and middle ages, the legend endured in the tiny Austrian village of Mixnitx that a local cave held the bones of dragons, and possibly living ones too. These villagers knew nothing of the existence of cave bears, and the passages gradually became known as “dragon’s cave” (Drachenhöhle).

The truth is that Drachenhöhle was perhaps the most heavily concentrated tomb of cave bears in the whole alps, with an estimated 30,000 skeletons at its peak. At 925m in elevation, it looks like a typical cave from its hillside location, with a wide 12 meter by 3 meter entrance. However, this easy accessibility means that Drachenhöhle was used by successive generations of hibernating cave bears. In some places, the phosphate sediment from old bones was 12 metres deep. Drachenhöhle also contained the oldest human remains ever found in Austria, dated back to 65,000 to 31,000 years ago. Evidence of the first human exploration dates back to 1387, and in 1904, a cave tourist called Jean Striemer was stuck in Drachenhöhle for 3 days, before 2 female friends remembered that he had gone there and brought him food and water.

Many of the Drachenhöhle’s bear skeletons ended up Landesmuseum Joanneum in the large Austrian city of Graz, although a vast amount were ground down for phosphate by the Germans in World War 1. Nowadays, this cave bear hotspot is a popular tourist attraction. It’s completely undeveloped, and visitors must step over several dangerous piles of rocks during the tour. There’s no cost of entry… except maybe your life. The reward is the chance of seeing numerous ancient cave bear bones embedded in the cave floor.

| 10 | 2020: fully preserved mummy found |

In 2020, some Russian reindeer herders were going about their duties on Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island in the northern Siberian wilderness. Suddenly, they spotted a matted bundle of fur by a melting, muddy riverside. It was a snarling bear head, but not just any snarling bear head. It was a prehistoric cave bear corpse with its nose intact and its teeth so sharp that they seemed to be preparing for a bite. Later, scientists dated the mummy back to 22,000 to 39,500 years ago, and discovered that its fur, internal organs and soft tissues were astonishingly undamaged.

Recently, a woolly mammoth mummy and a preserved 40,000 year old wolf’s head have been found on the same islands. It was the first ever intact cave bear discovery, but probably not the last. Coincidentally, a juvenile cave bear was discovered around the same time, but hundreds of miles further south in Yakutia.

After decades of reconstructions and guesswork, we now have true visual confirmation of what a cave bear looked like in its prime. The mummy is so well preserved that you can see how the cave bear’s head differs to a modern brown bear – high and long versus round and compact. It’s early days yet, but the next plan is to find extractible DNA, and food in it stomach to analyse the diet. Russian scientists from the North-Eastern Federal University (NEFU) in Yakutsk are now on the task. Could clone armies of cave bears patrol the alps in 20 years time? We’re getting ahead of ourselves here – they still have the woolly mammoth to take care of.

Leave a Reply