| 1 | Almost impossible to find |

With its natural habitat being the vast, endless wilderness of Tibet and the Himalaya, the Tibetan blue bear is widely acknowledged as the most elusive brown bear subspecies in the world. Compared to the American grizzly or European brown bear, or the ferocious Siberian brown bear, blue bears are almost impossible to track down, which is fitting given their rare blue-tinged coat.

The rareness can be overstated by the internet at times, as a couple exist in zoos in Japan. But if your life’s mission is to find one in the wild, then good luck. Like the snow leopard, you don’t find blue bears – blue bears find you. The Himalayan ranges are so vast that a trek to mountains such as Annapurna (11th highest in the world) can take 10 days, with the same true for the Nepalese side of Everest. This is the blue bear’s natural turf, and if the blue bear wants to stay hidden, then that’s what will happen.

Not once have Western scientists managed to capture a wild blue bear, to perform the detailed analysis of the subspecies they desire – the best they’ve achieved is the fur and pelt. A Western explorer could spend years in the mountains without ever finding one (which might be best for his health).

| 2 | Unique bear features |

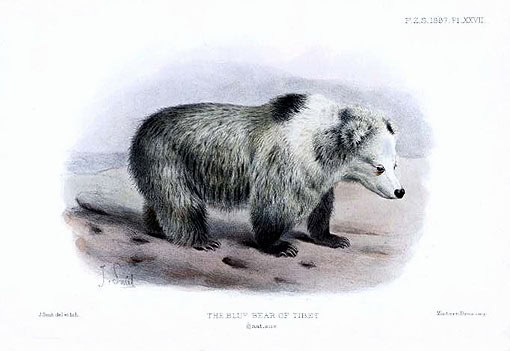

Among the 9 Eurasian brown bear subspecies, the Tibetan blue bear is easily the most unique looking. The species isn’t quite as blue as its Smurf brethren, but it’s undeniably the bluest bear around, despite being part of the brown bear species overall. The bulk of its fur has a blue tinge unique to any bear, but there’s also a cream-coloured section that starts at the chest and spreads into a collar. The colour varies too, with particularly dark or light bears often being spotted.

Among the 9 brown bear subspecies, the Tibetan blue is middle of the pack for both height and weight. Its fur is particularly long and shaggy, a thick coat against the harshness of the Himalayan winter. Its ears are also very prominent, which could be an adaption to the echoing soundscape of the wide Himalayan valleys.

Another brown bear subspecies roams the same Himalayan turf – the Himalayan brown bear (predictably). This bear has more typical brown fur, though slightly lighter that a Eurasian brown bear’s. You might guess that the subspecies are barely any different, but genetic analysis has confirmed that the Himalayan brown bear and Tibetan blue bear are completely distinct. The blue bear is its own entity entirely, and a magical one at that.

| 3 | Low population, but not extinct |

The Tibetan blue bear is so elusive that its population size is unknown, although one good estimate is 5000. One threat is the superstition of the local Tibetans, who consider the bears to be worldly manifestations of evil spirits, and commonly kill them on sight.

Likewise, traditional Chinese Medicine recommends bear bile as the perfect folklore remedy. The bear lacks an official conservation status, and pessimistic environmentalists have occasionally claimed that the bear is already extinct, but thankfully, sightings continue to the present day. The most recent by a Western was in July 2019, in a remote Himalayan valley. They’ve also been filmed by cameras placed in Chinese national parks, as shown in this link, which features perhaps the greatest, most magical picture of a Tibetan blue bear you’ll ever find.

This article discusses an author who was updating a nature book called Lonely Planet’s China in 2020. A Tibetan driver encouraged him to visit a “magical valley”, and upon entering the monastery there, he noticed 4 stuffed yaks hanging alongside the pelt of a fearsome shaggy creature. The monks informed him that this was a Tibetan blue bear, and to quash all doubt, the monk whipped out his high tech smartphone, and showed him a picture he had recently snapped of 3 living blue bears. It was a mother and two cubs, walking through the same valley side by side, and the author confirmed the picture’s authenticity.

| 4 | Source of the yeti myth? |

In 1960, famous mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary set out to the Himalaya to establish once and for all whether the yeti really existed. He was the first man to conquer Everest in 1953, and upon reaching Nepal, he visited a monastery called Khumjung, standing above a mountain village called Namche Bazaar. The head monk present him with a pelt he insisted was the fur of the mythological yeti. The local Nepalis could not be shaken in their belief that this creature prowled the valleys. After gaining the monk’s permission to take the pelt away for testing, and returning to New Zealand, several anthropologists reached the same conclusion: that it was the fur of the elusive Tibetan blue bear.

The theory undeniably makes sense, as Tibetan blue bears are so rare that they could easily fit with the elusive nature of the yeti. If you picture one standing on its hind legs, the unusually shaggy blue bear even looks similar to the iconic yeti image.

On the other hand, this was a single piece of evidence collected from a single mountain community. Does it really prove that the yeti is a purely mythical creature? It’s worth noting that Hillary didn’t rule out the yeti’s existence himself: “the yeti is probably a mythological creature, but I would be delighted to be proved wrong. There’s no doubt that the monks in the monasteries and many others believe in its existence”.

| 5 | Finally sighted by Westerners (2013) |

In 2013, two conservationists called Eddie Game and Hamish Reid set out to cross the Tibetan plateau, a vast wilderness north of the Himalaya packed with wolves, yaks and fierce winds. Their mode of transport was mountain bikes, but one day, while they sat by a river to recharge their energy, Hamish triggered a loud crack as he stood on a patch of ice.

Immediately, he heard a far louder sound: the roar of a distant bear. The seemingly gentle beast had been sleeping, but now, it was hurtling towards them with the speed of a freight train. Game and Reid did what they were trained to do and sounded their air horn. The bear kept running. They sounded the air horn again, and this time, the bear seemed to pause, 80 feet away from the explorers.

Game and Reid simply prayed, knowing that the air horn was exhausted. Then, with some apparent uncertainty, the bear turned around and headed back to the river. It stopped, glanced back at the men, and headed up the sand dune. Then it stopped and glanced again, before making a final decision and vanishing into the endless plains of Tibet.

Would Game and Reid have survived if they hadn’t sounded the air horn in time? Who knows, but what’s certain is that they encountered the incredibly rare Tibetan blue bear, as the high definition pictures they captured show. See them here.

| 6 | Quest for the blue bear |

In the 1960s and 1970s, Jing Wangchuk, the third king of Bhutan, was said to be fascinated with the blue bears roaming his kingdom. Yet despite owning the lands, he had never once managed to see them personally. So in 1971, the future fourth king hired Malcolm Lyell, the manager of a Dutch gun company, to venture into the wild and track one down, providing him with a map with territory marked as “sanctuary, blue bear”.

Lyell was the only European man granted permission to hunt for the blue bear in Bhutan. As expected, Lyell failed to locate a single bear, but he came extremely close. One yak herder he spoke to in Tasi Markhang (northern Bhutan) reported that a blue bear had been seen prowling the maize fields just the previous night. Several herders claimed to have witnessed blue bears in days gone by, calling them shy and reluctant to interact with people (despite regularly stealing their livestock). The trick, they informed Lyell, was to tie up a yak as bait and wait for the bear to emerge from the shadows.

By the expedition’s conclusion, Lyell had become equally fascinated with the blue bear. At the encouragement of Bhutan’s equally bear-mad fourth king (who took over in 1972), he returned on two further expeditions in 1974 and 1975, but failed in his quest for the blue bear once more.

| 7 | History of the blue bear |

The Tibetan blue bear was first classified as a subspecies by English zoologist Edward Blythe in 1854, after remains of its pelt and fur were brought back. But what about even earlier?

The three bears in the region surrounding the Himalaya are the Tibetan blue bear (right on map above), the Himalayan brown bear (left), and the desert-adapted Gobi bear (top). It’s believed that the latter two diverged from all other brown bear species around 650,000 years ago. This was during the Pleistocene epoch, when the Himalaya were the most heavily glaciated in their history. With the bears separated into islands by vast towering glaciers, and mountain passes which could no longer be passed, they were free to evolve in strange new directions.

Meanwhile, the Tibetan blue bear is far more recent, despite its appearance having grown far more distinctive than the Himalayan brown bear’s. Blue bears share a common ancestor with the North American grizzly bear and the common Eurasian brown bear, and diverged only 343,000 years ago. During an interglacial period, a group of bears separated from the pack and travelled east towards the Tibetan plateau. There, they began the slow transformation into the blue-coloured superstars we know today. These genetic facts were discovered in a scientific analysis from 2018.

| 8 | What we don’t know could fill a book |

The consistent theme with the Tibetan blue bear is blank spaces in the record. This bear is so mysterious that we barely understand its diet, mating patterns, or favourite sleeping patterns. The blue bear’s favourite habitat is believed to be near the treeline of high mountain slopes, but nobody is 100% sure. They’re said to travel extremely long distances compared to normal bears, in search of mates, but nobody is 100% sure. In addition to pinching livestock, the blue bear is believed to eat pines and nuts, but nobody is 100% sure.

That said, the Tibetan blue bear is known to be a particularly carnivorous bear, closer in diet to the feared East Siberian brown bear than the Eurasian brown bear. It’s known to enjoy a meal of marmot and pika, a small Himalayan mammal which looks like a mountainous rabbit. By contrast, the Himalayan brown bear is said to be a peace-loving vegetarian.

More mysteries include a supposed fact mentioned in Chinese articles that 1500 people are killed every year by blue bears, which seems unlikely, and whether blue bears are most active at sunrise or sunset, or whether the whole day is their playground.

Despite the rapid technological advances of humanity, the knowledge we’ve gained of physics, distant solar systems, medicine and technology, this bear somehow evades our grasp.

| 9 | A relatively dangerous bear |

In every picture ever taken, the Tibetan blue bear looks as cuddly as your favourite teddy bear, but statistics show that it’s the most dangerous animal in the Tibetan region. They kill as many livestock as the average brown bear, and local herders have many a tale of wandering down the familiar corridors of their house to find a blue bear standing right in front of them.

To gain entry, the blue bear tends to smash in a door or window, which often leaves a trail of blood from cuts to its paws. Local herders commonly erect wire mesh to prevent bears from entering their huts, while others use firecrackers or even electric fences. Like the American black bears digging pizza out of bins, the blue bear has the intelligence to suss out where readily available food sources are.

Summer is the peak danger time, the time when Tibetan herders move to a second, high altitude home to carry out their duties. Occasionally, they’ll descend to their winter home to check on things, and this is when they typically come face to face with the blue bears that break in during their absence. Summer is also the peak season for gathering mushrooms and berries high in the mountains, sending the herders headlong into bear habitat.

Elusive they may be, but blue bears cause their fair share of mayhem.

| 10 | Occasionally found in zoos |

Most zoos don’t tend to advertise their brown bear subspecies. The word “bears” alone is enough to draw in tons of smiling families eating ice cream. But Tibetan blue bears appear in a few zoos around the world, including China, as shown in these cute images. Unfortunately, the bears’ happy expressions mask the fact that they’re begging for food, and in 2011, an equally cruel video of a blue bear in Japan’s Oji zoo did the rounds. It was titled “Headbanging Bear vs Frolicking Students,” and showed a bear dancing around near the glass while two little girls cried with delight. But that bear was actually “bouncing”, a classic sign that bears are overheating.

Go back over 100 years to 1916, and you have this obscure newspaper cutting, revealing that Philadelphia zoo had just become the first on US soil to acquire two Tibetan blue bears. It mentioned their “white-tipped, blackish hair, which gives their fur a hoary appearance and imparts a light bluish tinge“. The zookeepers were relieved, as they were sceptical about whether Tibetan blue bears were even real! They also had trouble with the Germans, who controlled 75% of Atlantic animal shipping at the time. Whether they lived a happy life is unknown.

There’s no doubt that Tibetan blue bears were put on earth to be a mystery bear, not a sad zoo showcase. The only time a blue bear should beg is if he sees an Everest mountaineer eating a chocolate bar!

Leave a Reply